“Oppenheimer” (2023) – “It worked.”

It did.

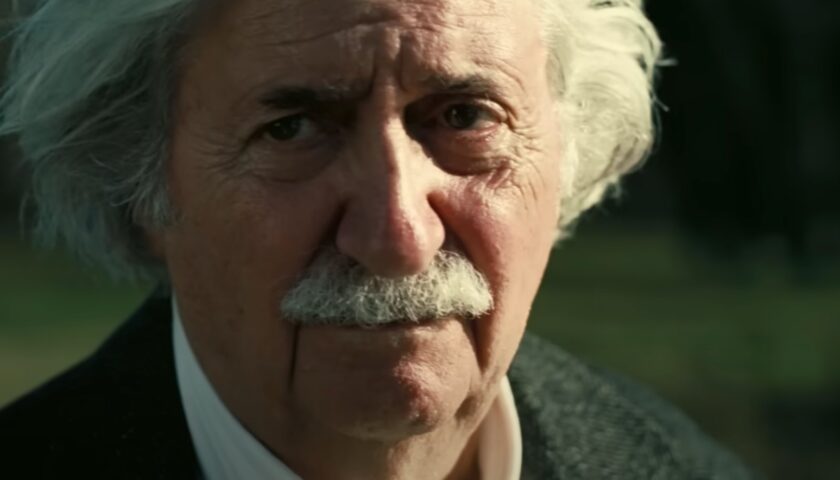

J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) was a physicist teaching Quantum mechanics at the University of California, Berkeley when United States Army Corps of Engineers Major General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) taps him to lead The Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, N.M., a mission to develop the first working nuclear bomb in a race against the Nazis during WWII.

History proved Oppenheimer was successful, as the U.S. first crossed the ominous finish line with the plutonium-based Trinity Test on July 16, 1945. Less than a month later, the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, and WWII was over.

The moral implications of U.S. President Harry Truman’s actions on Japan will be questioned forever, and director/writer Christopher Nolan’s new film “Oppenheimer” explores the ethical dilemma about J. Robert and his team’s work in New Mexico versus the application of their invention.

Well, the film explores this idea for a portion of his 180-minute runtime.

In typical Nolan fashion, “Oppenheimer” is a technically gripping production. He presents his familiar signatures of playing with time and frequently introduces rapid-fire edits that whisk the audience to and from wildly different locales and instances.

However, Nolan also obsesses over political and bureaucratic theatre that entangled J. Robert after the war. Yes, these events (or versions of these events) occurred and are part of the man’s legacy, but these moments digress (or are tangential at best) from the core story, which is the building of the first nuclear bomb.

After watching the film twice, I estimate that the aforementioned administrative after-the-war muddle captures about 60 to 75 minutes of screentime, and this extended theme – indeed – grants a larger perspective of Oppenheimer. However, ultimately, its inclusion feels like unneeded noise that bloats the runtime to three hours, where the last 50 minutes becomes a puzzling space of office infighting, backroom dealings, paperwork, and ambient lighting. There is a method to Nolan’s madness, and he does close a loop introduced during the first act. Debating Oppenheimer’s role in the upcoming atomic arms race – after the war – raises pacing issues and additional scope that feels better suited for a series. How about a 6-hour, 6-episode series?

Nolan based his screenplay on the 2005 biography “American Prometheus” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, and the big-screen creation covers The Father of the Atomic Bomb’s life in three ways.

- The man’s career through his university education, teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Manhattan Project

- His personal life, including his relationship with his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt), a love affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), his brother Frank (Dylan Arnold), and all their connections with the Communist Party

- The political fallout after the war, especially his entanglement with Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), a United States Atomic Energy Commission member

The film brushes an artistic flair in spots, and the moments are welcome sights. For instance, the picture’s second shot features raindrops falling on a puddle while our lead stares at their impact. Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema repeatedly display similar examples on the screen, like lit embers floating from fiery explosions in space or Oppenheimer simply tossing drinking glasses into the corner of a room to witness the spread of the crystal shrapnel. It takes a beyond-brilliant mind to lead the United States in Quantum mechanics, and Nolan and Van Hoytema use these visual tools to communicate the scientist’s thoughts.

The pair also shift the on-screen events between color and black and white throughout the picture. Quite frankly, it’s difficult to determine the reasoning, but the answer – that I found afterward – is online. Still, I recommend watching the film without this knowledge and seeking it out after you leave the cinema.

Conversely, Nolan leaves less to the imagination when Jean and J. Robert engage in a couple of raw sex scenes, ones that solidify the film’s R-rating. These moments may be new territory for a Nolan picture, but they demonstrate Oppenheimer’s more primal urges. He was a flawed man with his infidelities, and these scenes pragmatically indicate his indiscretions rather than have the audience wonder with interpretations.

Otherwise, Nolan makes the audience work. During the first two hours, Oppenheimer advances from student to professor to Manhattan Project director while frequently connecting with Frank’s communist friends, Jean, and his soon-to-be wife Kitty. Meanwhile, he needs to design this impossible engineering puzzle, let alone solve it, so he meets dozens of academic experts, scientists, and engineers to map out a plan that ultimately costs two billion dollars over three years. (Incidentally, Google says that’s 37.4 billion dollars in today’s money.)

It’s a whirlwind of faces, which are easy to remember, and names, which prove more difficult to recall, as they collectively design the specs and, of course, the dangers.

From an actor’s perspective, Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, Rami Malek, Tom Conti, and Matt Damon (Groves) play vital parts in Oppenheimer’s career and in designing and constructing the Los Alamos facility and the bomb. It leads to the infamous Trinity Test, which Nolan recreates on screen. The 20-minute sequence, quite frankly, is the only reason to see this movie in the IMAX format, as the anxiety during the countdown and the detonation is a stressful horror show through the emotional anticipation, jump scares via wicked booms, and the frightening fireball awe.

Nolan and Murphy also deal with this invention’s destructive force and future implications that “will outlive the Nazis.” After three years of mathematical, scientific, and engineering toil, the implausible goal is achieved, and our film director and lead display the dichotomy of Oppenheimer’s achievement as the Father of the Atomic Bomb while he also realizes that he’s “The Destroyer of Worlds.”

Two brief, highly effective scenes drive home this infinitely important point, as we see a hero’s welcome that feels straight out of Maverick (Tom Cruise) landing on the aircraft carrier at the end of “Top Gun” (1986) versus Oppenheimer’s guilt over the victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The ethical implications of Oppenheimer’s invention are the emotional pulls of the film. Still, Nolan detours into broader issues, specifically, the escalation of the hydrogen bomb program, a subject handled in the most uneventful and dry collection of office discourse.

The first two acts devote plenty of minutes to this subject. Still, Robert Downey Jr. – inexplicably – seems to receive the most screentime during the movie’s last hour in a puzzling way to conclude an Oppenheimer biopic. Eventually, Nolan gets to the point during the film’s final five minutes, but witnessing courtroom drama with Downey Jr., Jason Clarke, James D’Arcy, Dane DeHaan, Casey Affleck, and more doesn’t seem the best use of anyone’s time, especially after Nolan churns our insides with stress during the Trinity Test.

Oppenheimer and his team are in a race to beat the Nazis to the bomb, but we never feel the stress of the contest. Never.

However, Damon should consider himself in the Oscar race next spring, as he gives – hands down – the film’s best performance. Damon’s Groves is Oppenheimer’s never-ending and constant caustic push from above to complete the job, but he almost always sprinkles in traces or heaps of humor while barking orders. Oscar chatter will probably speak Murphy’s way as well, although this critic isn’t completely convinced. Murphy looks nearly as thin as Christian Bale in “The Machinist” (2004), and he convincingly portrays, through poise and delivery, an incredible intellect who attempts to stroll in between the raindrops of Communist friends, sexual temptation, and governmental roadblocks to build the world’s most dangerous weapon. Unfortunately, the man gets wet. Curiously, during the second half of the film, someone chastises J. Robert about his several character flaws, however, other than Oppenheimer’s infidelity, we don’t see this list of imperfections portrayed on-screen. Instead, we see an ambitious man performing his job while navigating the choppy waters around him. So, I don’t know if Murphy communicates this intended range.

As for the film, this critic wished that Nolan shortened his range to wrap up this story in 120 minutes and cut out all of the Lewis Strauss story. All of it. Instead, the film spends too much time diving into editing and storytelling choices that feel like Oliver Stone’s “JFK” (1991), but debating theories and clues of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s demise are inherently more compelling than discovering who attempts to remove J. Robert Oppenheimer’s security clearance. This is especially true when the latter built the first nuclear bomb. There’s too much at stake to needlessly tangle the narrative into a paperwork tale as an extended epilogue.

However, Nolan, his team, and the actors pour prodigious efforts into retelling Oppenheimer’s personal life, career direction, the planning and the building of the bomb, and the moral comeuppance. So, overall “Oppenheimer” is an important film, and it works.

Yes, it worked…but not without misgivings.

⭐⭐ 1/2 out of ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Directed and written by: Christopher Nolan

Starring: Cillian Murphy, Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, Jason Clarke, Tom Conti, Josh Hartnett, Matthew Modine, and Kenneth Branagh

Rated: R

Runtime: 180 minutes

Image credits: Universal Pictures